‘Get over it’: Primark resists move online despite pandemic shock

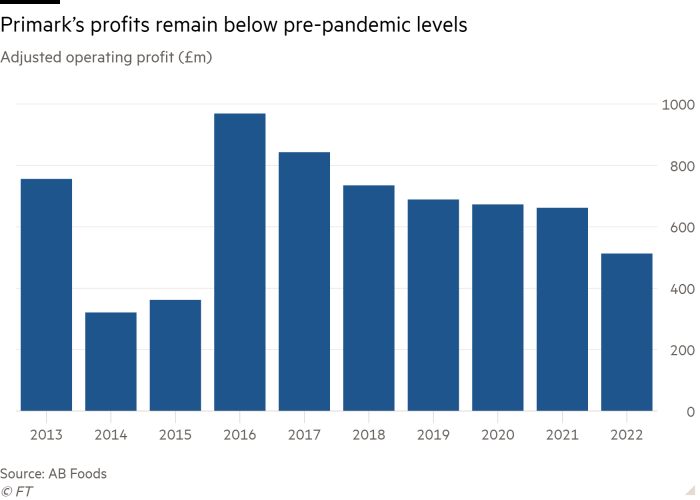

As Covid-19 rampaged across Europe in 2020, Primark’s managers could only watch as online rivals muscled in to supply T-shirts, hoodies and pyjamas to its locked-down customers. With no online sales channel, the discount clothing store was faced with total closure and burning through GBP100mn of cash each week. The retail powerhouse that was forecast to make GBP1bn of operating profit in the year to September 2020 ended up making less than a third of that.

But even the toll of the pandemic has not persuaded Primark to finally embrace online shopping. George Weston, chief executive of the chain’s owner, Associated British Foods, told the Financial Times that while it was “a nice hypothesis” that Covid had changed the industry for good, sending shoppers permanently online, the growth in Primark’s market share compared with before the pandemic suggested that was not correct. Weston is adamant Primark “is and always has been a high street retailer” and said an evolution into a home delivery ecommerce business was simply not going to happen.

“At our price points and our basket sizes [online] doesn’t just take some of the margin, it takes all of it,” he said. “Get over it,” has been his blunt message to those who advise otherwise. Still, surviving the sudden closure of 191 UK stores and hundreds more in Europe was a challenge the business would rather not repeat.

“We grabbed the revolving credit facility and put it into our own bank accounts, looked at the terms and conditions of our private placement notes and told our food businesses to generate as much cash as they could,” recalled Weston.

As the weeks of lockdown turned to months, other British clothing retailers, such as Marks and Spencer, expanded their online offerings. Primark considered using a marketplace such as Zalando or Asos to sell through, but swiftly ruled it out. “The only reason to do it would have been to clear stock to raise cash,” said Weston. “Once the stores started to reopen, we knew we would not have to do that”.

The company’s sales are still below pre-pandemic levels in some European markets but Primark said this was often because the overall apparel market had contracted and that its share of the market had actually increased in many countries. But some believe Primark’s online position is untenable in the long term. One person who has worked at the fashion chain pointed out that the UK and several of its other key markets were relatively mature and its core customers increasingly expected to be able to shop online.

“They cannot end up as the only retailer in the world [that] doesn’t offer [ecommerce]”, the person said. Even Walmart in the US, a low-price retailer initially reluctant to trade online, eventually decided it “had to get into it and learn to make it work”. Primark’s only concession to online selling so far has been a click-and-collect trial of childrenswear from 25 stores in parts of England — around 6 per cent of its total estate.

The mini-trial was so popular the company’s website crashed when it was launched — and it could be extended. Richard Chamberlain, an analyst at RBC, said click-and-collect services that drove footfall into stores had been tried by retailers such as Sports Direct and H&M, but the sales added had been useful rather than transformational. He said it was “hard to see [ecommerce] as anything other than dilutive to margins”.

Online sales also pose dangers for the store estate. “If 20 per cent of your sales migrate online, your cost base in the stores doesn’t change,” the former Primark insider said. “They just don’t want it to happen”. By contrast, Primark hopes that click-and-collect might drive a degree of “top-up” shopping in stores as customers pick up another GBP1 pack of bangles or a 90p hair brush along with their order.

The chain is not alone in shunning online shopping. Supermarket groups Aldi and Lidl have stayed away from ecommerce.

So-called “variety discounters” such as B&M and Home Bargains in the UK and Action in Europe have also struggled with the economics. Primark, along with other discounters in all sectors, has regarded opening new stores, often in new countries, as a more reliably profitable way to grow. “We have trialled [online shopping],” said Mat Ankers, chief financial officer at Poland-based discount clothing retailer Pepco. “But our customers want to shop with us in our stores, and stores remain the key driver of our growth”.

The company is opening hundreds of new shops each year in central, eastern and southern Europe. Similarly Primark, which was established in Dublin in 1969, is planning to add Romania and Slovakia to the 14 countries in which it already operates.

One of Primark’s stores in Madrid attracts crowds of shoppers (C) Marcos del Mazo/LightRocket/Getty Images

The fashion chain’s approach to international expansion is usually to start small and learn. In the US it planted its first flags in Boston because of the strong Irish-American presence there.

But as it quickly became clear the clothes were popular with Hispanic customers, it opened stores in Florida. In New York, managers noticed that a disproportionate number of customers were from lower income groups, so Primark initially focused on the outer boroughs of New York, rather than flagships on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue. This gradualist approach — and its refusal to follow peers online — is helped by its ownership structure.

AB Foods is majority owned by the Weston family, conservative long-term shareholders who have nurtured the retailer as part of an old-fashioned conglomerate that also includes sugar production and groceries. Weston said it was “really noticeable that some of the world’s most successful retailers have come from small communities”, namechecking Zara owner Inditex, which has grown from its remote outpost on Spain’s Galician coast to become the world’s biggest fashion retailer. “It gives you a certain humility.

You have to have an interest in what other people want rather than just selling them what you’ve got”. The former Primark insider said the management team was largely “just left to get on with it” by the AB Foods senior team. However Weston noted: “We understand how to internationalise a business, so every now and again we’ll say ‘don’t touch that it’s hot’,” he added.

For now, delivering parcels of clothes to customers at home, and the expensive business of processing the ones they send back, is set to remain in that “too hot” category.